When I took the book to the counter, the assistant remarked on the oddness of the cover:

Which was interesting because the day before, at the Futura Science Fiction convention (attended so poorly that a standard-issue police box would have suited us fine, never mind a TARDIS), one of the panels mentioned a book shop which deliberately obscured all its stock's covers with a paper bag on which a summary was hand-written. The thinking behind it is that cover design is a marketing tool which encourages ever-tighter genre descriptors and alienates potential readers. I'm in total agreement: much cover art is derivative and/or terrible, and it is alienating. There's a lot to be said for the old uniform Penguins.

Sometimes there are interesting experiments: I collect Jane Austen editions, and use them in my teaching about 'popular' and 'high' art. I show the students these copies and some other Austen editions, from too far away to read the names and titles, and invite them to guess what kind of novel is inside.

Then we talk about genre, marketing and how our reading are shaped by these kinds of expectations: the 'adult' cover art for children's novels also get an airing. It's a fun class and one which gets students talking about reading as a social and economic activity, as cultural capital and social positioning. At Saturday's convention, we were given several free books which looked like typical SF novels. One of them was described on the back as 'military SF': a sub-genre of which I've heard but never wanted to read. To me, military SF evokes Heinlein's neo-fascism and the kinds of terrible 'find planet-meet aliens-kill them all' stuff beloved of America's most imperialist phase, rather than Joe Haldeman's The Forever War. So you see, genre and cover art can repel as much as it can attract.

But back to Banks. The quick chat with the bookshop assistant formed a kind of sad little coda (for me: she didn't appear to know who he was and I didn't want to break the bad news) for the weekend. The Futura event (I couldn't resist an SF conference named after a typeface) was overshadowed by Iain's death - for me as a reader but more painfully for the writers gathered. They'd lost their brightest star, and in the case of Ken MacLeod, a very close and longstanding friend. I didn't want to dig around in his grief during the kaffeeklatsch session (buying a convention ticket does include access to a man's grief), but he spoke very movingly and amusingly about their long association during his reading and presentation. Banks reciprocated: he makes a point of praising MacLeod's unpublished poetry in his last interview. We got the sense that the late 1970s was great for them: before Scotland's industrial destruction at the hands of Thatcher, Banks and MacLeod were bright, educated, hip young literary gunslingers. Active on the hard left, fond of a drink, full of the Scottish virtues of socialism (MacLeod described their politics as 'Socialism within, Anarchy without', which seems pretty seductive to me), contempt for the cosmopolitan and determined to put all this into their work, they seemed to have had a ball. Banks had three SF novels rejected before deciding to write a 'mimsy mainstream Hampstead novel' as MacLeod put it, and he worried that it was a betrayal of all he stood for. No need to worry: The Wasp Factory was hailed and condemned in equal measure as a nasty piece of outsider tyro viciousness.

The convention itself was enjoyable, though it did feel a little like the last months of the airborne party Douglas Adams wrote about in The Restaurant At The End of the Universe: all the ingredients were there but the audience was slightly lacking. Literally: despite the publicity's exhortations to sign up for the various elements as numbers were limited, the total turnout was in the 30s at most. So I felt a little sorry for the authors (Ken MacLeod, Ian MacLeod (no relation) and Adam Roberts, plus several others of whom I hadn't previously heard because I don't read many graphic novels, or what Pratchett affectionately calls Big Comics). They are eminent and popular authors, and here they were in a cavernous space talking to tiny numbers of people: 5 of us in the Banks kaffeeklatsch. The day before, Adam Roberts (who writes cerebral SF and is a Professor of 19th Century literature and culture) gave a TEDx talk in Parliament to 1000 people. Yet here he was, discussing Kant and reading from his new novel, in which a cow mournfully (spoiler: and unsuccessfully) tries to persuade the man with the bolt gun that cows should be Turing Tested before meeting their ends in the abattoir. Roberts is interested in culture's representations of animals and aliens as (perhaps necessarily) anthropomorphised devices to talk about ourselves: the truly alien couldn't be comprehended. He read the piece in an Ermintrude voice, and I mentioned philosopher Peter Singer's article Heavy Petting, in which he suggests that bestiality really isn't so bad in comparison to just killing animals for fun and food. It's a provocative and enjoyable piece.

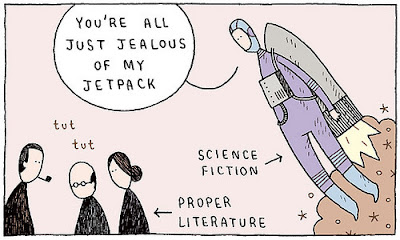

Apart from the author stuff, I went to a panel which discussed whether SF is 'mainstream', which was very enjoyable. There's no answer of course: SF is certainly on prime-time TV, elements of SF surface in other popular genres, and literary fiction sometimes appropriates SF themes and tropes. Yet what is the mainstream? Is it critical approval? Canonical acceptance (I set books on academic courses: am I one of the 'them' who approves or disapproves?) Sales? What's so great about being mainstream anyway? Is anything mainstream in an era of targeted marketing and ever tinier sub-genres? Certainly there's an element of any genre's readership which defiantly rejects being popular – very reminiscent of my other hobby, record-collecting. Some people would rather their favourite music was never heard by the 'sheeple', which I think is a moronic attitude. I mostly listen to music that isn't popular, but I regret it: I'd rather my favourite singers and authors made a living than starved to death in a garret to increase my cool quotient amongst a tiny band of obscurantists.

I also bought a couple of books and was given a couple more. Who could resist a pulp-homage zombie attack novel set at a Star Trek convention? Not me, especially not for a shiny £1. I also bought a book in which a man in search of a fabled lost Carry On film finds himself joining a shadowy underground army of resistance fighters. Can't remember the title, but it sounds promising.

And I won a raffle prize - at 37, I'm no longer a loser in life's lottery! A copy of Ian MacLeod's Wake Up And Dream in a slipcase, signed in a limited edition of 100. It's very beautiful and I'll cherish it, though I really don't like the wider culture of limited edition things. I spent quite a lot of money buying the only copy of his The Summer Isles I could find, which was also highly limited, signed etc etc. Very lovely, but I wish an edition was freely available to potential readers who don't have money. The same goes for beautiful William Morris work, De Morgan tiles, or the new collection of James Joyce work in progress, Finn's Hotel: copies range from €350 to €2500. Beautiful things, whether they're books, wine, hand-knitted jerseys or paintings are expensive and slow to make, but when the objects become fetishes, they offend my democratic instincts, especially when they're valued solely for their rarity rather than their intrinsic cultural value.

Of course this was also an opportunity. These three writers are amongst my very favourite contemporary authors and we had the chance to chat to them without any pressure or time constraints. I bagged them all as future guest speakers at the university too: we're trying to strengthen our cultural activity and these authors can contribute strongly to the sense that there's intellectual life here. A larger event wouldn't have afforded these possibilities, yet I was acutely aware of the social boundaries slightly blurred by the accidentally-intimate scale of the proceedings. We turned up for the quiz which was meant to round off the evening: it didn't happen, and probably 12 people stayed in the bar. My little group of academics. Some non-academic fans. The authors. I didn't feel comfortable joining the authors' group because it felt intrusive, especially as we'd spent the entire day talking to them about their craft, the process, their ideas, Iain Banks and so on. And yet the other fans had no such compunction and enfolded the authors into their circle. Perhaps it was the financial relationship which inserted the awkwardness: we'd paid for their time during the day's events, so I felt quite strongly that stepping into their social space was presumptuous, as though it communicated a sense of 'I've paid £25, so I have the right to engage in drinking banter with you whether you like it or not. '. This, by the way, is why I oppose student fees so much: a customer/provider relationship is alienating. It erects social and intellectual barriers between what should be a unitary group of truth-seekers.

So there I was, slightly absurdly drinking 4 yards away from the main attraction of the day, studiously keeping myself to myself. I can't speak for my colleagues of course, let alone the authors and the fans so I have no idea how they perceived the social situation but I was well aware of the absurdity. Perhaps I'm just too middle-class and repressed for ordinary social interaction. Mark Corrigan's spirit is most definitely hovering above me as I type this. Perhaps that's why I read SF: the classic loser's choice of reading – or it used to be until the nerds took over the levers of popular culture, to the bewilderment of people like my parents who spent my teenage years trying to ban SF from the house.

OK, I should stop now: this is a rambling and random collection of thoughts. Futura: fun. Great to meet and talk to interesting, thoughtful and talented authors. A social minefield though. And now it's time to go to the launch of a history of The Hegemon. Which includes photographs taken by, well, me!