My experience of record collecting is not much like this. I go into record shops, ask for Field Mice 10" LPs and endure the scorn of the famed Record Shop Git.

In fact, much like this:

(Although he is right about those particular bands). I read High Fidelity when it came out and felt that Hornby rather uncomfortably knew me far too well. I went to see the film too, and watched at a 90 degree angle, craning to see what records were on the shelves, which essentially proved Hornby right about us. My sister observed at the end of the film that I was 'just like Rob'. She then thought better of this comparison, having pointedly noted that 'he gets a girlfriend in the end'.

So yesterday, I droned on about record collecting and Walter Benjamin's piece about unpacking his library. Today, I thought I'd point you towards Jean Baudrillard's The System of Objects, and in particular the section 'A Marginal System: Collecting'. Although he doesn't explicitly say so until a long way in to the essay, his concentration on the 'passion' of collecting is derived from Freud's work on fetishisation and sublimation. I'm not a Freud (or Baudrillard, or anything) expert so I won't push this point too far, but the essence is that the object need not be at all interesting or special to raise passion. Baudrillard's very keen to emphasise that while we're all obsessed with 'human' passions, our enormous investment in owning things goes relatively unnoticed.

they become mental precincts over which I hold sway, they become things of which I am the meaning, they become my property and my passionThis isn't use value: I will never again play some of my records, or re-read some of my books. Indeed a few of them will never be read – I wanted them as objects, not as functional carriers of information. Baudrillard differentiates between objects which mediate between the self and the world (refrigerators, spoons) and therefore can't be objects of passion but remain functional tools (although people with Object Sexuality might disagree, particularly the woman who left the Berlin Wall for a fence) and objects which can be wholly possessed, through which the individual constructs their senses of him/herself and a private world. Books and records, for me, fulfil this purpose at the moment though I must admit that my record collecting mania is fading and I'm trying to read more books than I buy.

Some objects can be both functional and possession, or move from one status to the other (usually functional to possession): for instance a chair which starts off being useful and ends up as an antique with a 'do not touch' sign on it, valued for its rarity, age or beauty. Something like this, for instance:

What is it?

(I took those pictures at Neuadd Gregynog Hall, the stately home owned by the University of Wales). It's an extreme example proving that anything can move from functional to possessive status. It can go the other way too: witness Dublin's mania for demolishing grand Georgian houses in the 1960s and 1970s as an anti-colonialist gesture, now sorely regretted.

Once a thing becomes an object, an extension of its owner's psyche, it is part of a collection, and cannot exist alone, according to Baudrillard.

And just one object no longer suffices: the fulfilment of the project of possession always means a succession or even a complete series of objects. This is why owning absolutely any object is always so satisfying and so disappointing at the same time: a whole series lies behind any single object, and makes it into a source of anxiety.I could own one record by The Field Mice, but it wouldn't be a collection and it wouldn't be significant.

Here's some Field Mice:

and my favourite track by their successor band, Trembling Blue Stars:

(They're dedicated to Ben, who thinks my affection for The Field Mice demonstrates everything that's wrong with me, and indie music).

The object becomes important once it is part of a network (Field Mice records, Sarah Records output, Field Mice records I won versus Field Mice records I don't yet own). The last bit is essential but also destructive. Possessing everything is I guess possible, but without the quest, life would be dull indeed. Not possessing everything though: that's awful.

And just one object no longer suffices: the fulfilment of the project of possession always means a succession or even a complete series of objects. This is why owning absolutely any object is always so satisfying and so disappointing at the same time: a whole series lies behind any single object, and makes it into a source of anxiety.That's what keeps capitalism going: the anxiety caused by not possessing the entire set, the latest phone or the best shoes – desire is always temporarily satisfied and simultaneously de-satisfied. This is the permanent state of the collector. And, says Baudrillard, the same goes for sexual relations. The person you're sleeping with right now is a unique being, s/he/it is one of a series of possession you're currently pretending constitutes the totality of objects you can possess.Your current lover is significant because s/he/it refers to all the other potential, abstract lovers. The same goes for my books.

It's complicated: that's why it's so vital and enthralling:

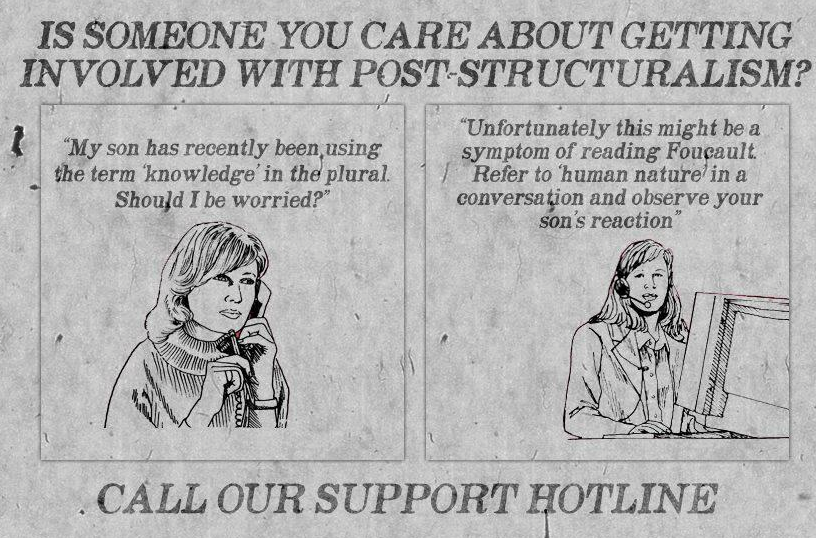

Our ordinary environment is always ambiguous: functionality is forever collapsing into subjectivity, and possession is continually getting entangled with utility, as part of the ever-disappointed effort to achieve a total integration. Collecting, however, offers a model here: through collecting, the passionate pursuit of possession finds fulfilment and the everyday prose of objects is transformed into poetry, into a triumphant unconscious discourse.Baudrillard sees collecting as a childish urge, in the purest sense: it gives the child a sense of structure and control in a world which affords the child no power or control. It's illusory, and immensely satisfying. Perhaps it's the same for me: I can fool myself that reading – or just owning – all these books makes me a viable human being, despite knowing that it's a very long time since it was possible to read all the books or know everything (i.e. everything Western European white men thought was worth knowing). There were several candidates: Thomas Young, Athanasius Kirchner, Alexander von Humboldt and a few others (this was of course before Foucault et al. got rid of 'knowledge' and replaced it with 'knowledges', but that's another blog).

But let's take Batman's advice and return to Baudrillard:

The child dominates the world through endlessly rearranging the collections: cars, dolls, worms, whatever. For most of them, puberty puts an end to it, but it re-emerges in forty-something men – known in the music business as £50 Man after his habit of appearing in a record shop and frantically splurging £50 every time. It wasn't like that for me. I read books obsessively but didn't own anything until my mid-teens. Getting to university, I began acquiring books and records on a grand scale. I looked down on £50 Man as a miser and an amateur. As I've detailed elsewhere, Cob Records in Bangor became the equivalent of a drug dealer with me as a desperate, dependent user.

In short, there is in all cases a manifest connection between collecting and sexuality, and this activity appears to provide a powerful compensation during critical stages of sexual development. This tendency clearly runs counter to active genital sexuality, although it is not simply a substitute for it.

Perhaps the single-sex education retarded my development even more than I suspected, because acquisition has become a depressing mainstay of my existence. I can dignify it by restricting it to goods with high cultural capital, but that's just snobbery. Basically, Baudrillard reckons that collecting is the unsatisfying sublimated expression of unfulfilled sexual desire required by losers (later on he calls it 'a tempered form of sexual perversion'). (My friends can add their observations in the comments box). He uses Freud's terms ('the anal stage') to categorise adult collectors as men (Freudians seem utterly uninterested in women's experiences) who require orderliness and accumulation to make up for what's lacking on the sexual front, with a side-order of defensive snobbery:

It is this passionate involvement which lends a touch of the sublime to the regressive activity of collecting; it is also the basis of the view that anyone who does not collect something is ‘nothing but a moron, a pathetic human wreck’.I used to tell people about the student many years ago who looked disdainfully at my office shelves and remarked 'You're just like my mum. She reads books and keeps them'. When I said I liked the sound of her mum, the student replied 'No, it's stupid'. Good god, I would remark: we're admitting students who have no interest in books, knowledge, learning for its own sake'. But according to Baudrillard and Freud, she got it right. She's psychologically healthy because she doesn't need to develop strong attachments to objects, whereas I'm compensating for some lack.

Baudrillard's post-Freudian insight is that the actual object doesn't matter at all. It's the object's existence in a chain or a network of other objects which the collector will attempt to acquire (though objects never possessed are as important as those which are eventually acquired). The collector adores each individual object and simultaneously desires all the others: the objects are the occupants of a harem:

the collector loves his objects on the basis of their membership in a series, whereas the connoisseur loves his on account of their varied and unique charm, is not a decisive one.

Collecting is thus qualitative in its essence and quantitative in its practice…there is something of the harem about collecting, for the whole attraction may be summed up as that of an intimate series (one term of which is at any given time the favourite) combined with a serial intimacy.This is of course a disturbingly gendered analogy which deserves its own critique at some point, but Baudrillard's point is that the collector maintains a degree of cognitive dissonance: when communing with one object in his collection he thinks he's monogamous, but really he's polygamous and can never stop adding to his collection. In a sense, he points out, being a collector is even easier than negotiating the complexity of human relationships.

Human relationships, home of uniqueness and conflict, never permit any such fusion of absolute singularity with infinite seriality — which is why they are such a continual source of anxiety. By contrast, the sphere of objects, consisting of successive and homologous terms, reassures.The problem with humans is that they want things. I'm told that they have feelings, and they definitely don't do what they're told. It's very inconvenient. They have, in short, agency. This is what the collector can't deal with. Object are much better: they don't move out when you're not looking, or object to your Marmite-based perversions etc. etc. They lack agency and therefore allow you the illusion of control (an illusion because the collection is never complete). I don't know if this is true, actually. I collect things and manage to maintain cordial relations with fellow human beings. As far as I can tell I'm relatively well-adjusted to the notion that other people have agency which needs to be respected. I haven't hobbled anyone to keep them in the house for weeks.

(don't watch this if you're of a nervous disposition)

For Baudrillard, collecting is a monstrous act of egomania which makes up for the inconvenient truth that humans are hard to bend to one's own will unless you take drastic steps as depicted above.

In the plural, objects are the only entities in existence that can genuinely coexist…they all converge submissively upon me and accumulate with the greatest of ease in my consciousness.Collecting is the defensive act of the loser:

But we must not allow ourselves to be taken in by this, nor by the vast literature that sentimentalizes inanimate objects. The ‘retreat’ involved here really is a regression, and the passion mobilized is a passion for flight.And it's hard to disagree when you meet adult Bronies (men who collect and obsess about My Little Pony) or see them stigmatised in the appalling and misunderstood Big Bang Theory, though my feelings about that show can wait for a future entry. Here's a clip from a show which explicitly addresses the tension between functional objects and possessed objects, though its resolution (Sheldon breaks the toy he's persuaded to treat as function, against his instincts, proving him right but still a loser):

In the end, any object in a collection, and the collection as a whole (though that's not strictly possible) is a mirror, a narcissist's fantasy:

what you really collect is always yourself.The series and the collection allow the collector to integrate with his objects in a hermeneutic state of perfection. Even if you reduce your collection to one perfect example, you're still a collector, because, JB says, that object is simply a referent for every other similar object, a realised version of the Platonic ideal.

This makes it easier to understand the structure of the system of possession: any collection comprises a succession of items, but the last in the set is the person of the collector.

Most strikingly, Baudrillard asserts that the unobtained object is the most important one in the collection. Its value to you increases because it will (perhaps temporarily) complete your collection. That one missing book in the series, that final Zimbabwean double-A side live recording is valuable not for any intrinsic worth, but simply because you don't have it. And yet you don't really want it. It symbolises death.

One cannot but wonder whether collections are in fact meant to be completed, whether lack does not play an essential part here — a positive one, moreover, as the means whereby the subject reapprehends his own objectivity. If so, the presence of the final object of the collection would basically signify the death of the subject, whereas its absence would be what enables him merely to rehearse his death (and so exorcize it) by having an object represent it.

madness begins once a collection is deemed complete and thus ceases to centre around its absent term.

If your psyche is completely invested in collecting, what happens when you have to stop because you've got everything? Quite often, collectors switch arbitrarily to other collections, demonstrating that the objects are worthless too them: it's the process that gives the collector meaning and value. John Laroche, the notorious orchid thief, wasn't always an orchid obsessive. First it was turtles, then fossils, lapidary, then tropical fish, collections he took up arbitrarily and dropped arbitrarily. Clearly the fossils, fish and orchids don't matter in the slightest: they're just a way of keeping score.

I don't think I'm that bad. Books are my delight, my leisure and my occupation. Music moves me emotionally. And yet: having these things is a major part of my enjoyment that I can't deny. It's true, though, that these things no longer drive me. When I was young, Cob Records would drip-feed my items I couldn't afford in one go. I happily spent more on books and music than on rent and food, to the extent that my finances were a mess. I'm no longer like that. The completist urge is still there, but paradoxically the easier it is to satisfy those desires, the less I try to. Now I can afford to buy most of what I want, I don't buy them, because the search felt more authentic than the possession. There's no pressure to find the missing Field Mice albums because I can now wave a cheque at a time of my choosing, rather than sacrifice other things to acquire them. Like I say: it's not the object that matters, though if any of you do have any Field Mice 10" and gig-only Stereolab releases, let me know.

Baudrillard knew I'd say that, by the way:

every collector who presented his collection to the viewing audience would mention the very special ‘object’ that he did not have, and invite everyone to find it for him. So, even though objects may on occasion lead into the realm of social discourse, it must be acknowledged that it is usually not an object’s presence but far more often its absence that clears the way for social intercourse.Ultimately, collecting is a denial of mortality for anxious, ephemeral Man (again, Baudrillard universalises habits he previously noted were a male domain):

What man gets from objects is not a guarantee of life after death but the possibility, from the present moment onwards, of continually experiencing the unfolding of his existence in a controlled, cyclical mode, symbolically transcending a real existence the irreversibility of whose progression he is powerless to affect.

the object is the thing with which we construct our mourning: the object represents our own death, but that death is transcended (symbolically) by virtue of the fact that we possess the object; the fact that by introjecting it into a work of mourning — by integrating it into a series in which its absence and its re-emergence elsewhere ‘work’ at replaying themselves continually, recurrently — we succeed in dispelling the anxiety associated with absence and with the reality of death.We collect because we cannot stop time, nor death. Which isn't far from my personal view that on the cosmic scale of things, anything we do is merely whiling away the brief, purposeless time between black nothingnesses. So why not obsess about Smiths records? It's better than committing war crimes or voting Tory. It's not totally grim, says Baudrillard: collecting integrates onrushing death into life, thereby allowing us to live, paradoxically, because collecting expresses and is driven by desire.

While I have my reservations about Baudrillard's argument (and it's early, heavily Freudian work which he superseded), I do recognise many aspects, including this section on book collecting:

Research shows that buyers of books published in series (such as 10/18 or Que sais-je?33), once they are caught up in collecting, will even acquire titles of no interest to them: the distinctiveness of the book relative to the series itself thus suffices to create a purely formal interest which replaces any real one. The motive of purchase is nothing but this contingent association. A comparable kind of behaviour is that of people who cannot read comfortably unless they are surrounded by all their books; in such cases the specificity of what is being read tends to evaporate. Even farther down the same path, the book itself may count less than the moment when it is put back in its proper place on the shelf. Conversely, once a collector’s enthusiasm for a series wanes it is very difficult to revive, and now he may not even buy volumes of genuine interest to him. This is as much evidence as we need to draw a clear distinction between serial motivation and real motivation. The two are mutually exclusive and can coexist only on the basis of compromise, with a notable tendency, founded on inertia, for serial motivation to carry the day over the dialectical motivation of interest.Put simply: sometimes my desire for completion overcomes my acknowledge lack of interest in a book's intrinsic artistic worth. It's offensive and decadent, especially in a time of deprivation, and yet I still do it.

There's a lot more to Baudrillard's argument, but too much of it is structured by a crude sexual division which makes me uncomfortable, and I strongly suspect I've outstayed my welcome. If you've got this far: thank you. I doff my hat to you. Here's Baudrillard's parting shot for people like me (and you?)

…he collects objects that in some way always prevent him from regressing into the ultimate abstraction of a delusional state, but at the same time the discourse he thus creates can never — for the very same reason — get beyond a certain poverty and infantilism.

So if non- collectors are indeed ‘nothing but morons’, collectors, for their part, invariably have something impoverished and inhuman about them.