On Monday, I ran the last class for the third years on Jilly Cooper's Riders, an awful but simultaneously fascinating book. Here's a brief and representatively excruciating clip from the subsequent TV adaptation:

The author strings words together efficiently enough to get from sentence to sentence, but there's no pleasure involved for us or, it seems, for her. The plot is risible, the characterisation would shame a Punch and Judy man and even the vaunted sex scenes are both embarrassing and less arousing than Cooper's reputation suggests. Nevertheless, it's a key text in the development of libertarian-feminist emancipation. Written in the 70s and published in the 80s, Riders makes strenuous efforts to get its readers to hate feminists (Hilary is a vegetarian, smelly, non-shaving, breastfeeding harridan with a wet husband who even cooks and cleans, but she transforms into a Real Woman once the aristocratic hero hits her, then they have sex: she's cured) while promoting a degree of sexual liberation.

This year, we also discussed readership and the social status of readers of popular fiction, particularly romance. One student was told off by a total stranger for reading such filth, while other said that their mothers were surprised that the things they read in the 80s were now officially sanctioned by a university. We talked about reading romance as a way to escape the demands on its mostly female readers by patriarchal society - so there is a feminist reading of Riders, which would annoy Jilly Cooper considerably.

Tuesday's highlight was our class on Eimear McBride's A Girl Is A Half-Formed Thing. It's one of the best books I have ever read. Written in a Joycean stream-of-consciousness, it tells the short and sad story of a young woman growing up in a fractured Irish family, alongside her brain-damaged brother, fundamentalist Catholic mother and various other characters. It draws on Beckett, Yeats, Joyce, Irish mythology, misery memoirs and a host of other influences, while unsettling generic and literary conventions throughout. The unnamed protagonist first has sex with her uncle at thirteen, and continues to do so throughout her life, as well as pursuing a series of increasingly violent sexual encounters with random men. McBride avoids the clichés of the field by never allowing the reader to define the protagonist. At times, she sees the uncle as abusive: at others the girl, then woman, seems in charge, even at 13. Her sexuality is formed by the need to differentiate herself from her brother (whose disabilities exclude him from social structures to his frustration and occasional relief) and from her mother. The central conundrum is that her means of defining and projecting herself are so self-destructive, particularly her sex life. She almost never enjoys sex. Instead, it brings her power (temporarily) and then relief ('I am sedated, she once says).

It's written similarly to Ulysses: completely from the disoriented and disorienting perspective of our damaged protagonist. For McBride, the neat and ordered language of realism can't bear the weight of experience. Here's a prime slice of the novel. If sexual violence is a trigger for you, skip this bit.

Dragging by the gruaig. He is I know. Across the stone my legs to flitters when you pulled me up the stairs. Breath. My eyes I can’t. Full of my own hair. Screaming. Shut up. Is that me I am I. I think. There’s a my body he push back. I’m. Fling rubbish thrown I am am I I. Falt. Where until I crack. Break my. Face. Head. Something. Smash. On a stump. Where on the back of my head on the back of my back my back crack that’s my eyes fucking up with tears. Scare me. Punch me there fright. Stop stop it you are who are I do I don’t want. I want to. Not this I don’t not for me what he will. You. Jesus. Got. Jesus on his knees pull me up pull me. Fuck. Not. Fuck not. Help. Grab me. Fingers of my skin. With his filth hands I hear. All the sounds tonight. Raddle fuck in my head. Tonight I hands up my. Knickers up my. Hurt. Not me Jesus. His nails too sharp are you. Did that. Did I make. Stop. Don’t don’t. I changed my. Jesus he. Not. No. Jesus me. Rips the I think dig them through my leg he. Spread fucking open up you sick fucking stupid bitch want the fuck you just like this I. Kick the kick. My heels dragging blood through the muck. Want to catch to prise to lift me. Save. Off off him fuck off me off me. He’ll. Pulls me up away. Kill. Me. Rake my hands I fingers in the dirt in the stones up my fingernails. Stones powder clawing them to. No. Get off. They’re off fuck knickers off. Fuck. Whore. You. He pulls like mad I I. Hear the sound. That fly. Zipping. Fuck out. Spring it out. Thighs in claws I vice. Rip m open. I make this. I make this. Undone he push my face hye pusk my head. My eyes flat of his hand. In the skull my. In the muck my crown of stones. Don’t break me open face open. Crushing I hear boines on done he up me fuck me. Smeeling he I don’t not do this I a don’t know he’s fuck me. Stucks the fck the thing in. Me. In. Jesus. I nme. Go. Away. Breeting. Skitch. Hear the way he. Sloows. Hurts m. Jesus skreamtheway he. Doos the fuck the fuckink slatch in me. Scream. Kracks. Done fuk me open he dine done on me. Done done Til he hye happy fucky shoves upo comes ui. Kom shitting ut h mith fking kmg I’m fking cmin up you. Retch I. Retch I. Dinneradntea I choke mny. Up my. Thrtoat I. He come hecomehe. More. Slash the fuck the rank the sick up me sick up he and sticks his fingers in my mouth. Piull my mth he pull m mouth with him fingers pull the side of my mouth til I no. Stop that fuck and rip. Scin. Stop heeel. Tear my mouth. Garble lotof. Don’t I come all mouth of blood of choking of he there bitch there bithc there there stranlge me strangle how you like it how you think it is fun grouged breth sacld my lungs til I. Puk blodd over me frum. In the next but. Let me air. Soon I’n dead I’m sre. Loose. Ver the aIrWays. Here. mY nose my mOuth I. VOMit. Clear. CleaR. He stopS up gETs. Stands uP. Look. And I breath. And I breath my. I make. You like those feelings do you now. Thanks to your uncle for that like the best fuck I ever had. HoCk SPIT me. Kicks. uPshes me over. With his brown boot foot. WitK the soLe of it on my stomik. Ver. Coughing my. Y hard. He. Into the ditch roll in gully to the side. Roll. I roll. For it. He. Turn on the. I. Hear his zip. Thanks for fuck you thanks for that I. hear his walking crunching. Foot foot. Go. Him Away.

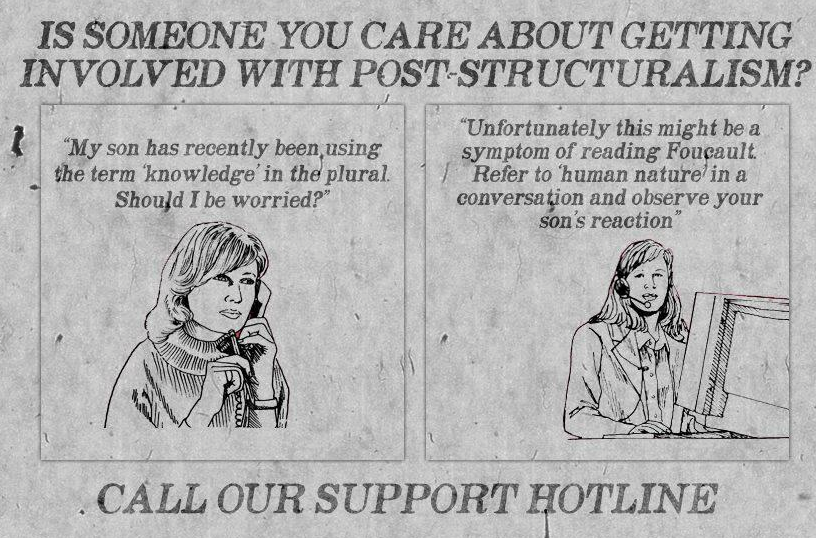

The novel's shot through with watery references, so it was no surprise to me that the protagonist drowns herself when her brother dies young, though some of the students weren't expecting it. Some of them hadn't finished reading it either (we have another week on it). It's hard to know what to do about 'spoilers' when teaching, but given this novel's modernist/postmodernist qualities, plot is hardly the central concern, so I don't feel too bad. Instead, we talked about its Irishness, about postmodern concepts of the Self (decentred, socially constructed, unstable), about Foucault, Butler and Kristeva. Perhaps a little too much for first-years but we'll reinforce it in future modules. I have visions of them turning up to Critical Theory next year and greeting each new theory with 'Done it!'.

I've rarely seen students so enthusiastic about a novel, particularly a text so difficult to read as this one. I'm going to keep it on the syllabus for a very long time to come.

Wednesday was the final seminar on Paradise Lost. Attendance is gradually declining as essays loom on the horizon, but they're a likeable lot and it's great to see how confident they've become when Milton terrified many of them a few months ago. We always get a few people deciding to write dissertations on his work, so we're obviously getting something right. I went fencing that night too: it was one of those evenings when things just worked, and I beat even the bright young stars despite being none of those things.

Yesterday was utterly gruelling. First off, office hours, followed by a two-hour student-staff meeting during which we went through the modules discussing what was working and what wasn't. Only a few students turned up, which was a shame, but those who did had plenty to say, positive and negative. I can't imagine that I'd have had the courage at their age, so I rather admire them. Then I nipped down to see my colleague who had a stroke. 8 months on and he still can't speak or move, which is utterly depressing. We were able to show him the proofs of his new book on Victorian spin doctoring and he responded enthusiastically. It's an excellent book and I recommend it to you all.

Finally, it was off to the Board of Governors: 3 hours of close scrutiny. There are some exciting things going on, and some less exciting things. I remain resolutely unimpressed by the government's total absence of education policy: vicious and evil as their instincts are, I'd rather they had a plan than a void. There's a lot of stuff I obviously can't tell you about, some of which is brilliant, but I can tell you that you can't trust management when it comes to industrial action (imagine my shock). According to them, between 23 and 16 people took industrial action recently. The technical word for those figures is 'bollocks'. We had more people than that on the picket line, let alone those who stayed at home quietly withdrawing their labour.

Marking today (as every day), but Friday started well when I secured 4 tickets to see Kate Bush in September. I'm presenting a paper on Dr Who and Star Trek on the same day, so I reckon I can construct a costume which won't look out of place at either event. I also got the beautiful new vinyl LP by The Nightingales and the Bullet For Gove t-shirt marking the lead track, which I'll wear with pride.

Because the Gales and Kate Bush would both hate it, here's a song by a band I'd never listened to before, and never will again: Quicksilver Messenger Service. They're largely forgotten, and rightly so: this is so inoffensive I can't remember a note of it 3 minutes after playing it.