Also, and on an astonishingly mundane level, my beloved Bridgestone Moulton bike is starting to show signs of age: it shouldn't be preying on my mind nearly as much as it is! At the moment I can't use the highest gear – the new chain (made up of two shorter ones) just won't engage with it, which is infuriating as I virtually never use any of the others. My local bike shop does its best but they haven't seen most of its odd-sized components before, and some of them are no longer made. Ideally I'd trade up to a Moulton NS Speed but I don't happen to have £16,000 plus change lying around and work's Cyclescheme doesn't quite stretch to it… I do have a boring normal road bike but that's playing up too. I don't know what I manage to do to them.

As for the rest of the week, it's been hectic but fun. My dramaturge friend Emi Garside popped up, so it was good to see her. I had two days at Swansea University, fitting in a little light external examining on their English and Welsh MA courses between walks along the beach, fine ice-creams and good company; I talked to students about resits and continuing projects, and I read some books. I enjoyed MT Hill's post-Brexit dystopian novel The Zero Bomb especially the vision of an illegal underground version of the NHS post-privatisation. Ben Aaronovitch's latest in the Rivers of London series, The October Man is set in Germany's wine country and was good fun - it's a novella that didn't add anything special to the overall series, but was very enjoyable nonetheless. After that I read Stevie Smith's 1936 Novel on Yellow Paper. It's been on my shelves for at least a decade, picked up for £1.99 from The Works. How I wish I'd read it as soon as I bought it. I didn't realise how much fun it was, nor how compelling the narrative voice is. The narrator is a businessman's secretary, Pompey, and the story is her jumbled thoughts on everything from the Jews for whom she feels some affection while also believing herself naturally superior (rather uncomfortable at this distance, though I suspect a fair representation of her class and time, and Pompey learns the error of her ways once she visits her German friends), the Nazis (against), suicide (for, in principle, and thinks it should be presented to children as a reasonable option), art, sex (very much for), marriage (rather undecided) and aunts (ambiguous). I moves between witty chat and genuinely profound. She performs constantly – as a family member, a friend, an employee – while knowing exactly how large is the gulf between how 'normal' people behave and how she wants to behave. The style is somewhere between Woolf, Flann O'Brien, Wodehouse and Daisy Ashford of The Young Visiters fame, and it's hard to tell how knowing or naive it really is. There are counter-Betjemanesque touches – like the image of the young woman lingering by the tennis courts in the hope that some young chap will propose to her – and Mansfieldesque ones when the Pompey takes a moment to examine her condition. I liked the line 'I do not like this riot of emotion. I do not like it at all'. Anyway - highly recommended.

Finally, I'm most of the way through Kate Atkinson's latest Jackson Brodie crime novel, Big Sky. Like all of the series, its power derives from knowingly flitting between literary fiction and detective fiction mode. I'm not sure the balance is quite right this time: the repeated reminders that the author and the characters are aware of what happens in crime thrillers are a bit laboured, especially when the plot – paedophilia and people trafficking on the Yorkshire coast – is so dark, contemporary and compelling. The bad men are nicely made, but the real triumph is Crystal, a damaged child who single-mindedly self-fashions herself into a trophy wife and becomes the moral core of the novel. Jackson himself, a great creation originally, seems to be a bit-part player to some extent, the vehicle for many self-deprecating jokes about his inability to connect with the younger generation (they all have mobile phones and don't talk to adults much, and you can't make them climb chimneys for a living) which sometimes shade into a sense that Atkinson herself is finding generational change a bit hard to take. That probably sounds harsher than I feel, but there is a problem here. The darker side of the novel is operating on the territory of David Peace's horrifying, political representation of South Yorkshire as a failed state, Red Riding Quartet and the best bits of it are equal to that series, but the jokes and cosier aspects keep detracting from the grimness.

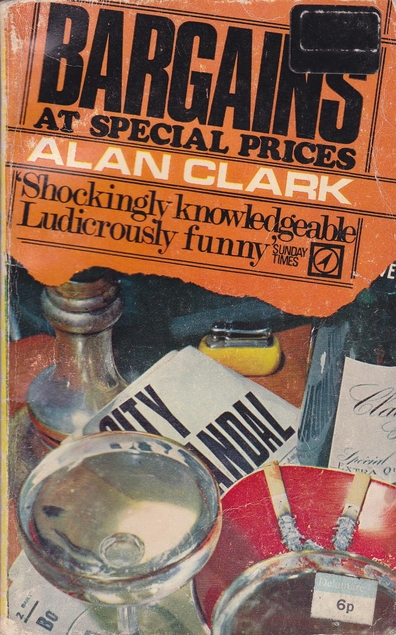

Next up – if I finish the manuscript I'm reviewing – is Kevin Barry's new one, Night Boat To Tangier. Amongst the new books acquired this week are Levy and Mendlesohn's Children's Fantasy Literature, David Runciman's How Democracy Ends and philandering MP Alan Clark's 1960 Bargains At Special Prices in a beautiful 1967 Arrow cheap paperback edition. The BBC showed a version of it in 1964 but I doubt any tapes survive.

2 comments:

I've loved Kate Atkinson for a long time - if I were to name my favourite novel of hers I'd have trouble nominating less than four (although my absolute favourite of her books, and the one I took to a signing, is Not the End of the World). But I wasn't quite sure about A God in Ruins; one section in particular seemed intended to be savagely satirical, but the mood that came across for me was less Swift and more Daily Mail. She's said that she thinks of AGIR as her very best work, and the scene where the old lady plays the piano in particular - which again doesn't quite chime with me (I mean, it's good...). Then there Transcription - whose main voice just got on my nerves after a while, in a way that wasn't allayed by the big reveal.

So I wonder, particularly given your comments. What I would say is that, for me, cosy/grim - or cosy-daft-jokey-meaningless/grim-tragic-unbearable-meaningless - is very much what she does; when it works there's a real sense of vertigo, of everything falling through (the trivia of life are meaningless in the face of the horror of death - and vice versa). I'll be sorry if it doesn't work in the new one.

Note 1: Actually I can get it down to three: Human Croquet, Case Studies and Life after Life.

Note 2: For the 'falling through' image see Robert Silverberg, "Sundance".

Post a Comment