So in the same spirit (though sadly lacking a publisher), I'm picking my holiday reads as I'm off next week. Two weeks in south-western Ireland. Hopefully some cycling, swimming in the Atlantic, climbing some mountains and the world-famous Puck Fair. It will, naturally, rain incessantly. I tend to read the Irish Times and the Guardian every day, and leaf through the

It's tempting to bring these two volumes, which I came across yesterday while unpacking another box of books. I also own a surprising number of works by Stalin and Lenin, despite not seeing myself as that kind of authoritarian lefty.

|

| Marxist-Leninist Philosophy (illustrated edition), Progress Publishing, 1987 |

|

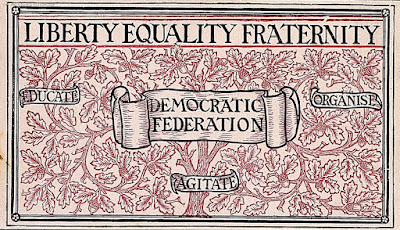

| A typical illustration from Marxist-Leninist Philosophy. They aren't all so eye-catching. |

|

| Early Lithographed Books. Sadly 'improper books' are not what you might think |

|

| One such improper book. |

Instead, this year I'm skewing the list towards Irish work. The only hardback I'm taking is Anne Enright's The Green Road: coming from an Irish family which is spread across the globe and has been known to fall out occasionally (hem hem hem), it seems fitting. Also Irish but from a different era and culture, I'll read Maria Edgeworth's 1801 Belinda: I'm a bit of a fan and am trying to read all her novels. Early editions feature the first interracial marriages in English-language literature: her racist father prevailed upon Edgeworth to remove them from subsequent editions. I'm also taking Paul Murray's The Mark and the Void, a comedy set in the world of banking during the crash. I shall stand outside the IFSC and try to raise a grudging laugh. As it's almost the centenary of the Easter Rising, I shall pay tribute to my ancestor Thomas who was in the GPO that week (taking part, not trapped while buying stamps) by reading Foster's Vivid Faces, his cultural history of the revolutionary generation. It will also help me with my current journal article about Brinsley MacNamara's scandalous The Valley of the Squinting Windows and Caradoc Evans's My People. I also take at least one old theory favourite: this year's choice is Foucault's The History of Sexuality volume one. To fuel my 1930s interests, I'm taking Margery Allingham's 1936 Campion novel, Flowers for the Judge. I read all the Wimsey novels recently, and gathered that Campion was Allingham's riposte to Sayers' creation, so thought I'd give her another go. I read The Tiger in the Smoke a few years back and thought it was interesting but very odd. I've no interest in crime at all, but do appreciate the machine-like beauty of a well-written genre piece. It's the same when I read the Jeeves and Wooster novels: the plots are negligible, you always know what's going to happen but the enjoyment is in the unfolding variations on the underlying formula.

What else am I bringing? The latest William Gibson because I like to keep up with his stuff even when I'm not convinced by some of the more self-consciously hipster elements; Le Carré's A Most Wanted Man, Will McIntosh's The Soft Apocalypse because I'm fairly convinced by the argument that the brutal capitalism we keep voting for is rapidly eroding not just the workers' lives but also those of the bourgeoisie or professional classes. As a very mild example, we're currently slated to move into great big call centre-style accommodation rather than shared offices of 3-4 people. Nobody (obviously) has asked us what we think we need or (even more obviously) what we'd like, but I see it as a concrete example of the proletarianisation of what was formerly the professions. Private and permanent space is now a privilege of the hierarchy: the Dean has a (university-owned) Steinway in his office. No doubt his deputies have the luxury of shelving, photos of their kids and all the little things that denote stability. Beyond the obvious stupidity of 12 person rooms for academics (try reading a book, let alone writing one there), and the impossibility of counselling a student, giving a colleague union advice or maintaining a personal library available for consultation when a student calls in, the removal of intimate space really does seem like a power play. In hot-desking situations, the work-space becomes the 19th-century factory floor in which the worker is depersonalised. On my pinboard and surrounding my desk are gifts from colleagues and students, collections of interesting artefacts, multiple piles of books relating to my current research and teaching duties, and a whole range of stuff which are extensions of me.

Without it all, we become interchangeable machines for teaching. We are no longer permanent and valued colleagues, but hands. We cannot reach for something interesting and useful if someone comes in for a chat. I probably won't be there, because without a permanent space and storage, I'll just stay at home when I'm not teaching. I won't be available for impromptu meetings, tutorials and consultations. Work becomes a chore and anything beyond the mechanical becomes a private indulgence to be kept apart from work – all the things that we middle-class people thought signified the value of our labour.

Without wanting to be overly dramatic about this, the hot-desking, call-centre model is essentially a fascist vision. It is fixated on efficiency, which to them means the absence of clutter and total visibility. It means no lounging about talking or reading (this also drives the total removal of books from areas of the library visible from outside) because that doesn't look like working. Their version of our work is people sitting at computers, not speaking to each other, typing. Typing anything.

For any other kind of activity, they should leave. Desks should be clear. Books and papers (the past) should be banished, as should mugs with jokes on them, family photos and all the other detritus of social intercourse. All these things – along with privacy and adequate space – are considered perks rather than necessities, of the kind that come with authority. We're told that these spaces are required for efficiency, but I've never heard of a manager applying these principles to him or herself, because they are important and need private conversations whereas we (the ones students turn to when they're suicidal, sick or about to be evicted or deported) are not and don't. So much for the academy's self-confident assertion of its' own structures: now we ape the corporate world, with depressing results.

What happens when this is done to us?

and there's a way to deal with cubicle farms too:

There's a gap between not having a permanent desk and the final ejection of the middle classes from secure employment, but I don't think it's as huge as you may think. The driving force in contemporary capitalism is to automate as much work as possible, and 'outsource' the rest so that we don't see the conditions in which our products are created, while boosting profits and share prices. The professional classes will join the workers in the bin marked 'no further use' and at some point we'll have to work out what to do with all these surplus people. That's the major failing of western market societies: having brought mass industry to an end, you're left with a large group of people who have nothing to do. Some can become hairdressers, some will serve us coffee, but there aren't enough skilled jobs to fulfil everyone, or to keep an economy going. Personal debt keeps it going to some extent, and Labour extracted just enough from the finance sector to dole out tax credits and a minimum wage, but these are just sticking plasters. The Tories are abandoning the benefits system and reducing corporate taxes so that the state won't be able to provide subsistence for the workless many – and they're in any case proclaiming that these people are unemployed because they're lazy shirkers, not because we've designed an economy based on exploitation wages and job exporting. Maybe we'll muddle on a bit longer but I can't see a good ending to this one.

Damn it. I was going to talk about books.