Last Saturday, I went to Stoke-on-Trent's Potteries Museum and Art Gallery for the annual Stephen Hagger Lecture (very sadly I was the youngest there by a good twenty years, and too many of them were from the National Trust wing of Morris fans). This year's lecturer was Fiona MacCarthy, design historian and biographer of Edward Burne-Jones, Eric Gill and William Morris, whose life and influence was her subject for the day. What links these three men and those around them is a commitment to art as a way of life: from the production of goods they evolved a philosophy of community, economics and politics – especially Morris. Stoke is the perfect venue for a lecture on William Morris. The industry which sustained the city was pottery: thousands of highly skilled workers producing globally-renowned items of astonishing beauty, and yet the city is a depressing sump of deprivation and unemployment now, and always was ugly: talk about alienation in action.

|

| Morris, by GF Watts |

Morris seems to have been a force of nature - constantly trying new things, full of energy and also enormous fun: his friend Burne-Jones's cartoons of him are affectionate as well as satirical:

I don't know if Morris's aesthetic appeals to you. I find the wallpaper beautiful but too busy, but the late period 'Arts and Crafts' furniture is really to my taste, and I'd love some of the ceramics designed by his associate William de Morgan.

|

| a de Morgan pot |

While I can't afford Morris furniture, glass, wallpaper or ceramics (and in the antiques context their cultural meaning is very different from what he intended), I can read his books and poetry, and I have a cheap facsimile of his astonishing version of Chaucer's work. His novel News From Nowhere is perhaps the most accessible.

|

| News from Nowhere |

It's a Utopian fantasy set in a Britain which underwent a socialist revolution in 1952. Classes, law, finance, private property and cities have been abandoned and the people live in agrarian, peaceful, small villages (we tend to part company here: I grew up in the countryside and it's more Cold Comfort Farm than communist paradise). The details are less important than Morris's underlying assumption that human nature is essentially altruistic. Our faults, he says, are those of industrial, capitalist urbanism. It produces competition, hatred, violence, oppression and (not incidentally, aesthetic ugliness).

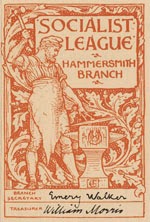

it is the allowing of machines to be our masters and not our servants that so injures the beauty of life nowadays. And, again, that leads me to my last claim, which is that the material surroundings of my life should be pleasant, generous, and beautiful; that I know is a large claim, but this I will say about it, that if it cannot be satisfied, if every civilised community cannot provide such surroundings for all its members, I do not want the world to go onReforming work will lead to beauty both internal and external, open to all. In this common weal, beauty is a condition of justice, and vice versa: the inhabitants, we're told, could not be happy knowing that fellow citizens are in prison, or trapped in loveless relations: mutuality is the key to social harmony (in contrast to the current Justice Secretary, who is scrapping the Human Rights Act and has banned sending books to prisoners). This was also the basis of his Socialist League

Simply the design of the membership card brings me to the real point of this rambling post. Art and labour brought together. The card is simply beautiful. It proclaims the unity of politics, life and art and above all it is optimistic. Like News From Nowhere, it assumes that the socialist future will transform people's lives for the better. When did we stop believing this? It's still there in Atlee's 1951 Festival of Britain (yes, the Tories took power in 1950 but the Festival was planned under the pioneering 1945-50 Labour government that founded the NHS and did so much more). After that? Not so much. Our supposed leaders are ashamed of the word socialist and whatever they do believe in, it isn't founded in optimism. Nor does it believe in a future which unifies love, life, joy, work, art and politics. Neither Labour nor the multiple far-left splinter groups offer anything positive. We spend our time accepting the ideological boundaries of neoliberalism and finding ways to mitigate the damage it does. I can't imagine the Milibands, Clegg, the SWP leadership or any of the others being able to understand the emotional or spiritual aspects of socialism that are integral to Morris's version.

Stunted by 'politics', they've lost us because they no longer have anything positive to offer beyond technocratic fixes. There's no way of life embodied in modern politics. There is in rightwing politics, but it too consists of joylessness: the Tories and UKIP spend their time saying 'no' to things – foreigners, human rights, the poor, community, altruism. That's OK: beyond Major's lazy fantasy of old maids cycling to communion, capitalist politics has always been about material acquisition. But it's not true of us. The left has forgotten that Marx, for all his talk of materialism, was funny, cultured and engaged with more than just economics - that's why his work is shot through with Shakespeare. Economics was part of his philosophy of life, rather than the other way round. Once the economics was sorted, he thought, our social, spiritual and philosophical ones would be too: happiness was the end, not simply material comfort. Morris knew this, and acted on it.

So why have we ended up with a political culture which would rather have us fulminating against 'scroungers', immigrants, Europe and each other, or competing over who can inflict most austerity to win votes rather than a labour movement which has a positive vision of how life could be. Last week the government gleefully announced that it would rather let African migrants drown than address the causes of their desperation. Every dead African is a vote reclaimed from UKIP, or so it hopes.

When did we forget that politics could be a vehicle for aspiration and happiness rather than a game of beggar-thy-neighbour? I believe, like Morris, that my fellow citizens are essentially altruistic and well-meaning, that given reform of our industrial, political and social structures this altruism could be liberated to achieve a better society. This is why I teach, and why I teach in an unfashionable ex-polytechnic in an unfashionable town (that and being essentially unemployable otherwise). The lesson of Morris is that all are capable of blossoming under and deserve justice and beauty – it's a socialism of humanity rather than just of economics: this isn't the 'art will civilise the brutish lumpenproletariat' argument of people like Matthew Arnold. It's the idea that intellectual and emotional freedom means nothing if it's reserved for the powerful or the 'swinish rich'. Hence Jeremy Deller's Venice Biennale painting:

It's called 'We Sit Starving Amidst Our Gold' as was inspired by Roman Abramovich mooring his mega-yacht in the middle of Venice, obscuring the views adored by Morris's hero Ruskin, without a thought for others. So here's WM, hurling Eclipse (the world's second largest yacht: two helicopter pads, two swimming pools etc.) out of the way. Morris really does seem to be having a moment.

I'd give up if I wasn't an optimist. I just wish there was a political party I could vote for that feels the same way. Suggestions on a postcard?

SPGB?

ReplyDeleteThey're great enthusiasts for Morris, and your post here could be printed in the Socialist Standard with hardly a word changed. And regardless of what you think of their (much-caricatured) political strategy, you'd find much to enjoy and agree with in their back catalogue, now mostly online.

Good piece. Did you know that as well as his tiles etc William de Morgan wrote some quite readable novels in later life? ("Joseph Vance" is worth seeking out, at any rate)

ReplyDelete